Love in the Time of Crisis

by Epoy Deyto

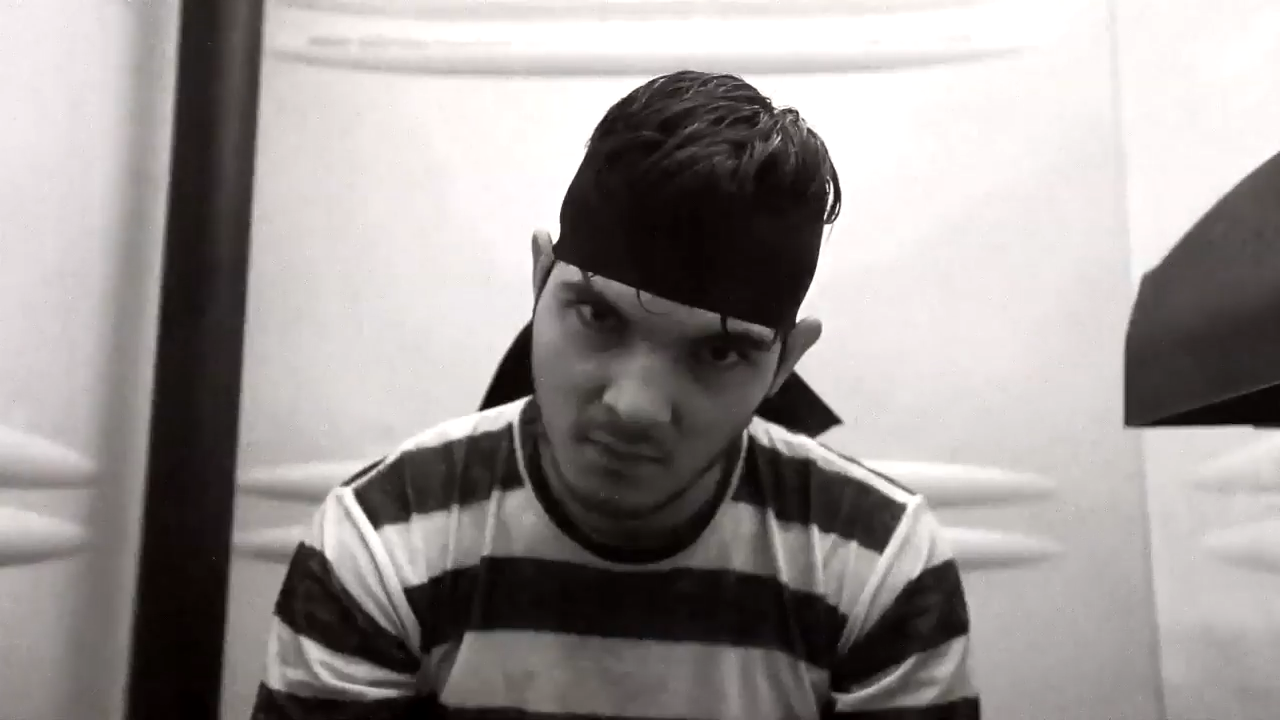

Above & below: images from Man in the Cinema House (Courtesy Bernard Jay Mercado)

Joshua Colet as the Man

It is not easy to love in a country like ours. Especially when contradictions highlight themselves in the most fashionable ways. In the past ten years, my cinema spectatorship has been halted by my real life disposition. Early in this decade we were just rising up from the effects of the global crisis, which never just dripped in trickles, but drowned us in waves. Prices hiked up, along with cinema prices. It was a good thing that film festivals tried to hold on and retained their 150 pesos (roughly $3) ticket prices—which is the price of a decent meal for one, and almost half the minimum wage in the nation’s capital.

Precariousness dominated love.

But then again, what is there to love?

Almost ten years ago, I attempted to contribute to Criticine’s “Love Letter” special edition, without knowing whether the website was still active after Alexis Tioseco’s and Nika Bohinc’s deaths. Its then editor entertained my contribution more than a month later. And posted it still a month later. Rereading the letter I wrote now, it pains me how much of it is half-conscious naïveté. Then again, I was too young to even capture and process the contradictions between my interest in cinema and my disposition in life as an urban brat from the slums. I find them even harder to resolve now.

I’m still interested in cinema, but with less gusto than my naïve young self. There are a lot of battles right now, and to choose which to fight is a privilege. A lot of us sought resolution by making sense of our own dispositions (personal or social) through our readings of films. I wrote somewhere, in response to Tioseco, that the first impulse of a critic must be never to be impulsive in the first place, but to stop, think, and combat all comforts of sentimentalism.

It’s not that I hate the idea of love. I just think that it’s too careless to make it an impulse. Especially if that impulse is going to be part of a critical assessment.

I don’t know, really, if in the present I’ve been focusing on the wrong things when looking at films. I don’t know either if those who are still actively writing about cinema in our country are looking at the right things. One can non-argue for plurality, that there’s no such thing as right or wrong, but I beg to differ.

If anything, the crises that fell on our country beg not just an answer but a solution. In the space of criticism, sentimentalism never really achieved anything outside of the conveying of personal experience. Most of the time it misses the subject of criticism too.

Nor is it that I love nothing about the film culture.

If there’s any film that I can say that I truly love that I’ve seen in the past ten years, it will not be by anyone known in the contemporary Filipino cinema canon. It is a short film by Bernard Jay Mercado called Man in the Cinema House released in 2015. Mercado described the film as a love letter to movie magic. I, on the other hand, see the film as a container of pent-up rage against the past and the present.

Man in the Cinema House is Mercado’s thesis project. It features Joshua Colet as the titular Man who is looking for his way out of the cinema house, and eventually, of the film itself, outside of the gaze of the security guard (Gabo Tolentino) who is set to lock him into the film. Later on, the man finds an exit through a portable toilet or portalet, which is a play on words: the film is treated as “portal” towards the outside of the film. During its premiere at the Film Institute’s public screening and thesis defense, the film was mixed with a live performance from Colet who happily cursed all the people at the venue, including the thesis panel.

I heard an anecdote that upon seeing it at the premiere, an alumnus remarked to his colleagues: “Is that it? Cinema is shit?” In a sense, the film captured something which warrants that reaction: the titular Man in the film is flushing a roll of celluloid film down the portalet. But what alumnus failed to see is that the film does not intend to propose a generic concept of cinema. It merely suggests a part of the solution.

My love for Man in the Cinema House was superseded by something stronger, and something more useful: its critique, weaponized through its form and content.

Man in the Cinema House is a historically aware piece. It refers to shit, yes, but that shit belongs to the present and an immediate past. Something that we need to get out from. As a film which is aware of history, we can also say that it is aware of its expiration. It is fearless against its supposed enemies as much as it is also courageous in facing its own future irrelevance.

It is this sense of fearlessness that somehow waned in the film scene in the middle of the last decade. Early on, the “new” digital filmmakers arrogantly posed for a no-holds-barred, fuck-all-be-all attitude in filmmaking. Their confidence was derived from the supposed potential given by the digital medium. This confidence is so dependent on digital technology that Lav Diaz even thought of it as liberation theology.[1] Like most social formations which have a ghost at their center, the digital liberation theology became less about its promised distributed autonomy, and has become something similar to an actual church, or cathedral, complete with bishops, dogmas, gatekeepers and all.

Man in the Cinema House and the reactions to it expose the crisis of cinema in the already crisis-ridden Philippines. The film positioned itself against the digital liberation cathedral, which profits from the maintenance of crises, instead of addressing it.

The cinema of the cathedral is the cinema of stasis. The moment when technology reaches its peak is when the images it produces became flat. There is no difference between a recent Lav Diaz feature and a recent Star Cinema blockbuster: both in the carelessness of form, the cynicism in content, and its political economic make-up. Diaz’s A Lullaby to the Sorrowful Mystery/Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis (2016), being itself a Star Cinema film, has reproduced (regardless whether it’s self-conscious or not) its “studio aesthetics,” which has been observably consistent with its recent films’ formal carelessness and cynical take on human agency. And it seems that everybody else outside the studio is following their example, a phenomenon that Man in the Cinema House predicted.

If this is the kind of cinema that we are getting on this side of the world, we might as well flush it out with all the other shit. We are still a long way from Man in the Cinema House becoming irrelevant. As far away as the end of the crisis from which the cinema industrial complex profits. Until the stasis breaks, what is there to love?

[1] See Tilman Baumgärtel, “‘Digital is Liberation Theology’: an Interview with Lav Diaz,” in Southeast Asian Independent Cinema, ed. Tilman Baumgärtel (Aberdeen, HK: Hong Kong University Press, 2012), 171–178.

Epoy Deyto is a media scholar and practitioner from Pasig City, Philippines. He currently writes film reviews for VCinema and on his blog Missing Codec. He was a fellow at the 2018 Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival & Festival Film Dokumenter–Jogja’s Film Criticism Workshop.